LQBTQ+

May 22, 2020

Editor’s note: Some sources who attend Mounds View and are part of the LGBTQ+ community wish to remain anonymous. Their names have been replaced with pseudonyms (“Student A” and “Student B”) to protect their privacy.

Objectively, things have certainly improved for the LGBTQ+ community. After centuries of criminalization and social stigma, it seems that society has taken a turn for the better in regards to acceptance and understanding of this diverse group.

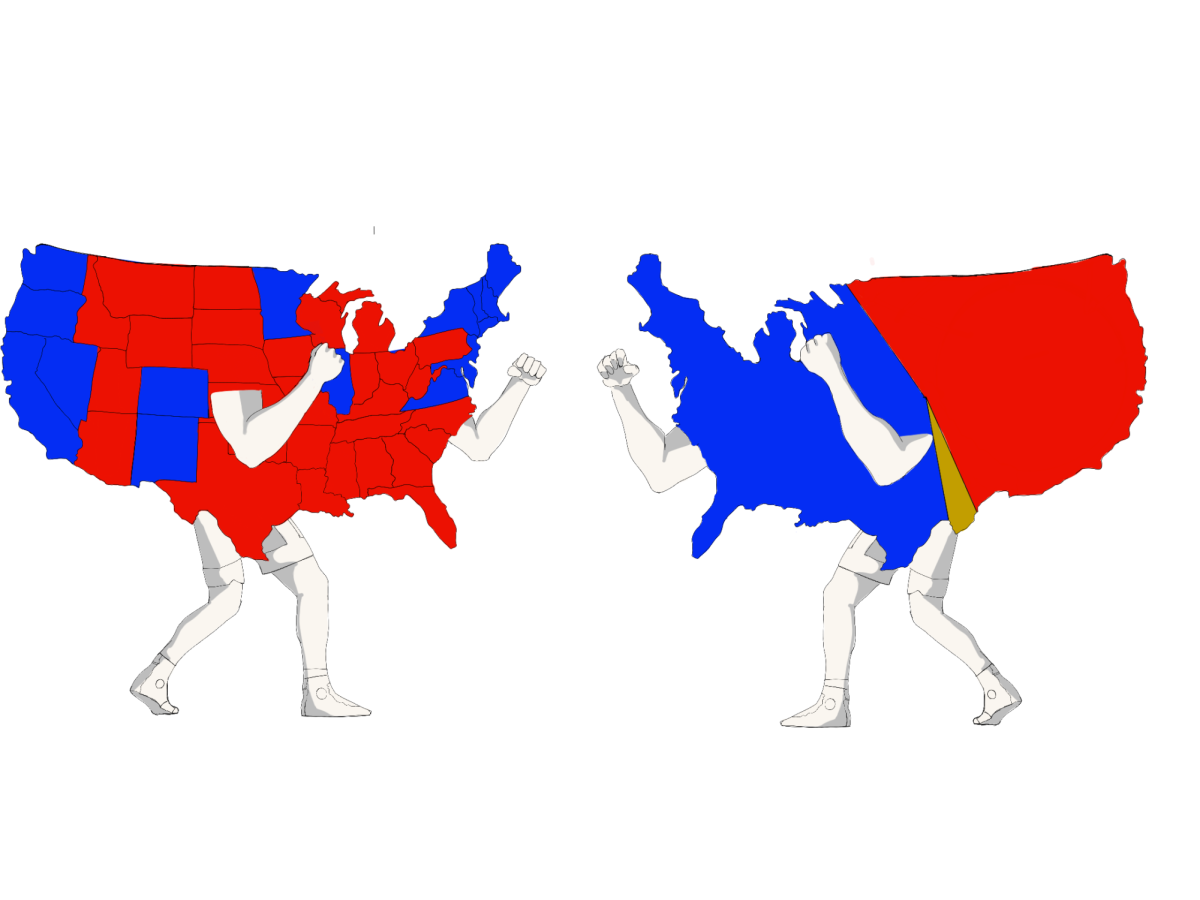

Many legal gains have been made in much of Europe and North America, with decriminalization of homosexual relationships in the United States occurring nationwide in 2003, the national legalization of same-sex marriage in 2015 and a general Supreme Court-strike down of discriminatory laws throughout the country. Additionally, acceptance is statistically on the rise. According to the University of Chicago, social support for the LGBTQ+ community has risen from 11% in 1988 to 46% in 2010.

These moves toward equality and legal protection are not a universal occurrence, however. In fact, there are seven countries that still impose life sentences for homosexuality and nine where LGBTQ+ people can receive the death penalty. Of course, the legal status of sexuality is not the only cause of violence against the community, with sexual orientation or gender identity-motivated crimes comprising about 19% of the 7,120 hate crimes reported in the U.S. in 2018, according to NBC. These official numbers may be shockingly low compared to the actual tally, with a Department of Justice report finding that 54% of violent hate crimes went unreported between 2011 and 2015. Of total estimated hate crimes, reported and unreported, 22.1% were caused by sexual orientation.

Alongside the threat of social repercussions, housing, service and employment discrimination based on gender and sexuality is still legal in some states, resulting in fierce and infamous legal battles such as Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission. So, even in the relatively progressive legal landscape of America, the LGBTQ+ community still faces significant risk.

But hate crimes and legal issues are not the only cause of strife, especially for LGBTQ+ youth. According to the Williams Institute, around 20 to 45% of homeless youth identify as LGBTQ+, while only 3% of male adolescents and 8% of female adolescents between the ages of 18 and 19 identify as LGBTQ+, as reported by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Suicide attempts, already the second leading cause of death for people between 10 and 24 years of age, are about five times more likely in LGBTQ+ youth than heterosexual juveniles, a report by the CDC states. Forty percent of transgender adults report having attempted suicide, according to a study conducted in 2015 by the National Center for Transgender Equality, and about 92% of those say their first attempt occurred before they were 25. Bullying, both in school and online, is more common in LGBTQ+ youth than their peers.

The LGBTQ+ community is faced with both progression and continued struggles in many spheres of life, and this mixed bag of experiences is reflected at Mounds View.

It seems that many LGBTQ+ students have had generally positive experiences at Mounds View. Students cite the active GSA group, supportive messages from teachers and accepting friend groups as their primary sources for comfort and positivity at school. “I think that the negative experiences that LGBTQ+ students experience at Mounds View come more from home life or out-of-school pressures,” said Student A, a member of the LGBTQ+ community at Mounds View. Students feel that things have improved for LGBTQ+ youth at school, and with the gradual inclusion of more LGBTQ+ history and stories in classes, students have the opportunity to learn more about their own community’s story and, for non-LGBTQ+ students, those of others.

However, negative experiences have not been completely eradicated. The use of slurs and fears of gossip, ostracization and stereotyping often lead to discomfort and unrest for LGBTQ+ students at Mounds View. “I was in class holding hands with this girl … the boy next to me asked if we were a ‘thing,’ and when I said yes, he called me the f-slur,” Student B said. Unfortunately, Student B is not the only student at Mounds View who is a part of the LGBTQ+ community who has been called a slur. GSA co-leader Jacob Olhoft, 11, recalls a time when he was playing his ukulele before school and was called the f-slur. “That was very appalling to me,” Olhoft said. “I was very shaken for the rest of the day.”

LGBTQ+ students might feel a lack of acceptance from the student body and reluctance to come out due to how some parts of the student body might react. “It seemed too good to be true that no one was staring at me or whispering behind my back,” said Student A, referencing their coming out to a friend. “I feel like [coming out] in middle school might have been better than doing it in high school,” said Tyler Routhe, 10. Routhe feels that because he came out in middle school, he has had more time to settle with his sexuality before coming to high school.

On the flip side, it is not always the social reaction that causes issues for Mounds View’s LGBTQ+ community. A sense of dissatisfaction regarding inclusion in various curriculums seems to pervade many students’ experiences. Many students have noted the lack of focus on LGBTQ+ issues in history and English classes which study materials centering around minority struggles as a sore spot in their education. “I’m not saying that we should restructure word problems in math to be gayer or anything, but if a teacher acknowledges diversity and shows that in the type of material and examples they give us … it’s honestly the best feeling to see that kind of representation,” Student A said.

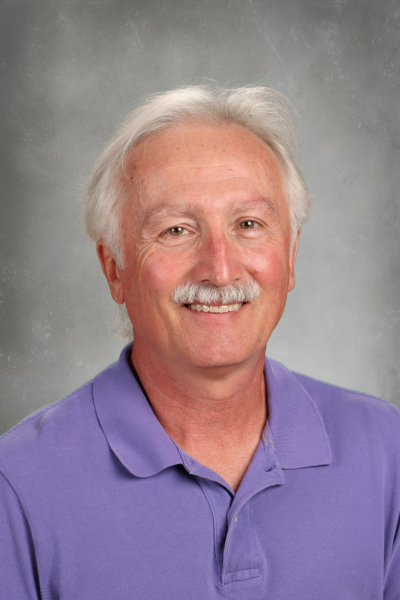

Even though some students feel that there is not much inclusion of the LGBTQ+ community in history or English classes, there is work being done to incorporate the LGBTQ+ community into lessons. “In AP [English] Lit [Literature and Composition], we usually cover poetry from LGBT authors,” said English teacher Rebecca Hauth-Schmid. While some students might not feel like there is much inclusion of the LGBTQ+ community in curricula, Routhe is one of the students who does see some of the efforts that teachers are putting in to incorporate diversity. “There’s especially a lot of teachers who are incorporating LGBTQ history in their lessons,” Routhe said. “I know we talked a lot about it in Hinseth’s [class], and especially with Nesset; she would always talk about the LGBT community.”

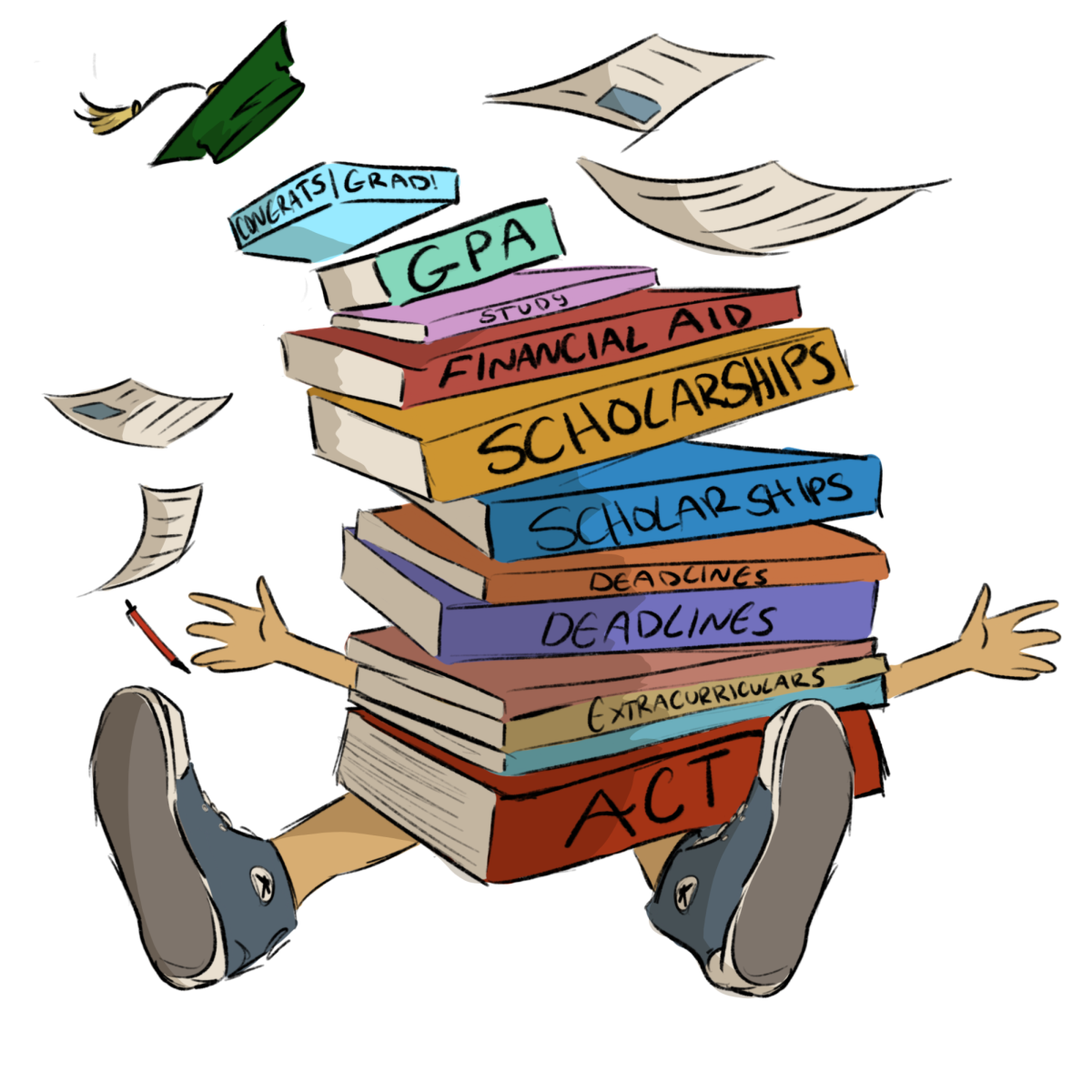

Alongside other social studies classes at Mounds View, AP U.S. History discusses LGBTQ+ stories at several points in its curriculum, such as the 1920s and the Civil Rights era, but some students express concern that this is not sufficient for providing a well-rounded education on the subject. “One of the tricky things is [that high school history classes] are survey courses, so they cover a long time period in a short amount of time,” said AP U.S. History teacher Alex Hinseth. “There are a lot of subjects that don’t receive enough [attention] because there’s no way to do it.” Aside from time constraints, there is also a problem when it comes to how history is studied. “The way we look at history, we need about 20 years to look back and understand and contextualize things,” Hinseth said. “So, with the LGBTQ+ movement, obviously there were things before the year 2000, but it’s really taken center stage in the last 20 years. I would say as time goes on, more will be included for that reason.”

The history department has discussed adding more comprehensive courses. “Every year, we talk about more in-depth courses to offer, but students aren’t necessarily choosing to take as many electives,” Hinseth said. “So, we can offer new courses and more in-depth studies on a lot of these topics, but the reality is we need enough students to register for them to run the classes.” On the other hand, many positive changes have occurred in the way history and social sciences are taught and the way their subject matters are received. “A goal of the social studies department is to be very inclusive, to talk about the absent narratives that are not included in normal textbooks or in traditional history,” Hinseth said. He also noted that students have become “more comfortable around the topics and discussing and debating and are a lot more respectful” when discussing LGBTQ+ history and issues in class.

Many of the decisions made regarding inclusion in social studies curricula come from the department and its teachers. “As a social studies department, we have quite a bit of autonomy,” Hinseth said. This is influenced by the few regulations and requirements regarding LGBTQ+ history in class, for beyond a few College Board and Minnesota State standards, the coverage of this strand of humanity’s story is often left to the individual school. “I’ve never felt any pressure one way or the other to teach more or teach less or anything around that,” Hinseth said. But, while Mounds View’s history department has made steps toward inclusion and goals for further in-depth education, other schools do not have requirements to incorporate diverse lessons in the same way or the teachers and administrations willing to promote inclusion in curricula.

Even more prevalent than concerns about curriculum focuses are questions about the indifference that many students perceive. “I also believe that it’s [LGBTQ+ issues] just being ignored by Mounds View, which is why no one seems to have an issue,” Student B said.

Though Mounds View Schools does have specific policies protecting LGBTQ+ students from bullying, harassment and violence, the student-led GSA seems to conduct much of the student outreach. “The GSA, theater and other activities have been so welcoming of this community,” Student B said.

Despite the issues LGBTQ+ students may face at home, in social circles, in the wider world and at school, many seem to have had positive experiences that have given them the opportunity to be out and happy among their friends. With the legal changes seen in the U.S., it is clear that some of the social stigma is wearing off, if only gradually. “Now gay people are confident in themselves, for the most part,” Student A said. “There’s a community now, a community that’s out in the open, that’s been hidden for so many years, and if you’re rejected by people you care about, well, there is a community to take care of you and make you feel loved.”

![[DEBATES] Prestigious colleges: value or hype?](https://www.mvviewer.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/buildings-1200x654.png)

![[OPINION] The dark origins of TikTok's looksmaxxing trend](https://www.mvviewer.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Copy-of-Copy-of-Untitled-Design-1200x675.png)

![[DEBATES] Prestigious colleges: value or hype?](https://www.mvviewer.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/buildings-600x327.png)