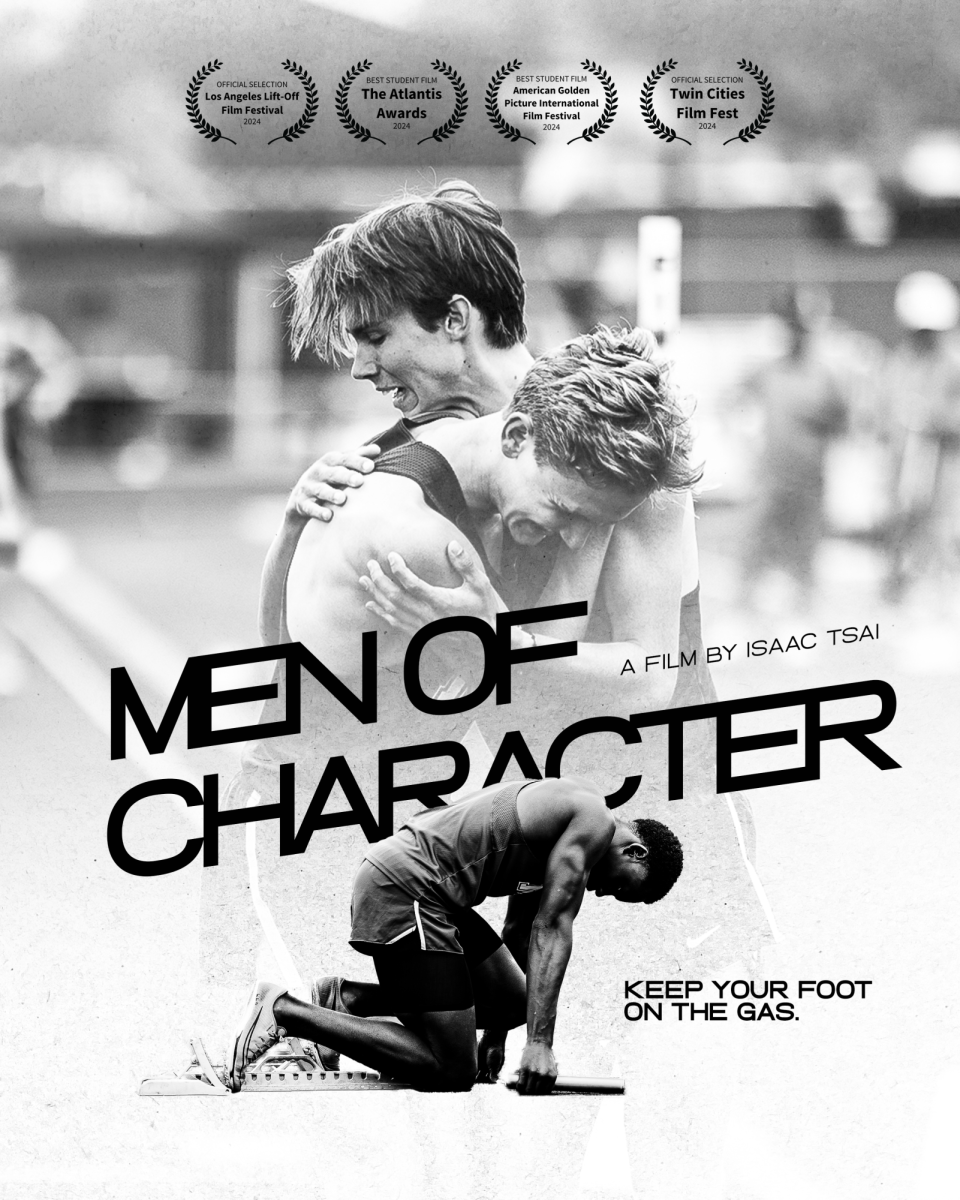

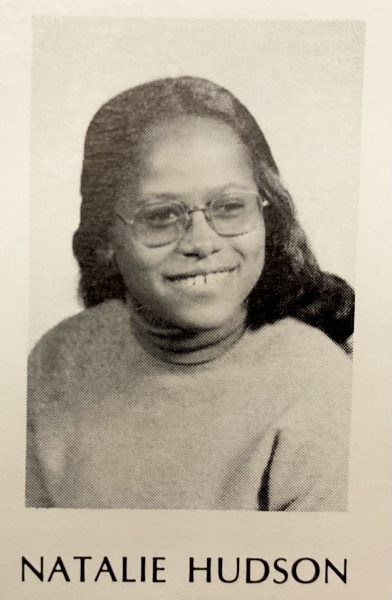

Chief Justice Natalie E. Hudson achieved a historic milestone last fall when she became the third woman and first Black person to lead the state judiciary. Her journey from Mounds View High School, where she graduated in 1975, to her current position as Minnesota Supreme Court chief justice, underscores her groundbreaking legal career.

Appointed to the role of chief justice by Governor Tim Walz last October, Hudson embraces her recently acquired position with immense pride, considering it “the honor of a lifetime.” She said the significance of holding the position as a Black woman is not lost on her. She also highlights how she strongly believes in the importance of representation in society. “It’s so important that people be able to see themselves in positions that they might aspire to and that all people be able to have that opportunity,” she said. “I think it’s important that we as a community recognize that talent and excellence comes in all genders, and all ethnicities, and all abilities, and in all sexual orientations. That’s all important for us as a society, and it certainly is important that our judiciary reflect the people that it serves.”

Reflecting on her years at Mounds View, Hudson recalls a positive experience but one that was also challenging and lonely at times. Looking through Mounds View yearbooks from the 1970s, the lack of diversity is evident. Hudson remembers only one other student of color in her graduating class. “While sometimes it was isolating, I also had a number of very good friends there, people that I still occasionally talk to to this day. And so, I can’t forget that part of it,” she said. She remarks that she can’t remember any racist incidents and feels the school attempted to create a welcoming environment.

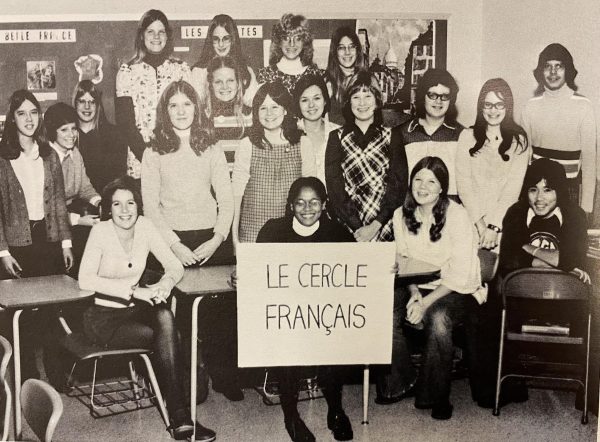

Nevertheless, Hudson said she did not always feel welcomed in school activities, which is why she did not join many. She did, though, participate in the French club and has fond memories of her senior year trip to France.

One aspect of Mounds View’s community that she remembers most is a very spirited environment, which she enjoyed. “I attended a lot of basketball games, a lot of hockey games and I suspect a lot of football games,” she said.

Hudson recalls her math teacher and Mounds View Basketball coach at the time, Ziggy Kauls, who the main gym is now named after. Another memorable teacher for Hudson was her English teacher, Dean Nelson, 82, who reached out to her after she became the chief justice. She considers him her favorite from Mounds View, saying he was incredibly encouraging and supportive of her and all his students.

After graduating high school, Hudson was eager to pursue college out of state. “I had family in Arizona — I still do — and I decided to attend Arizona State University there to be close to some family,” she said. “One of my good friends from high school was also going that direction, and so we decided to go together.” She was an English major, which she enjoyed and said prepared her well for law school.

Partially inspired by conversations with a relative in law school, Hudson said she decided to pursue law around her sophomore or junior year in college. When searching for a career, she wanted to find a way to make an impact and advocate for the underserved. “As I thought about what I wanted to do and looked at people that make a difference in our communities, it dawned on me that lawyers do that,” Hudson said. She moved back to Minnesota to attend law school at the University of Minnesota and graduated in 1982.

Hudson’s early years after law school were marked by her work with the Southern Minnesota Regional Legal Services. There, she provided civil legal services to impoverished individuals who couldn’t afford legal representation. Her commitment to public service extended to her role as the St. Paul city attorney from 1992 to 1994.

While she briefly worked in private practice, most of her career unfolded in the public sector. She spent eight years at the Attorney General’s office specializing in criminal appellate work and represented the state in cases before the Court of Appeals and the Minnesota Supreme Court. That’s when she found a love for appellate work, and that passion was pivotal for her in becoming a judge.

In 2002, she was appointed to the Court of Appeals. Her decision to transition from advocacy to the bench was driven by a desire to contribute on the defense side, recognizing the underrepresentation of women and people of color in the judiciary, especially on the appellate bench. After 13 years on the Court of Appeals, she was appointed to the Minnesota Supreme Court and has been an associate justice for the past nine years.

Now, as Chief Justice, she has taken on a role that she describes as challenging and exciting. “I have suddenly taken on a lot of administrative duties that I did not have before because I am actually leading the third branch of government,” said Hudson.

Navigating her career when there were very few female lawyers, let alone a woman of color, Hudson learned to persevere. “Much like I found in high school, I found mentors along the way. Many of them were white men because that’s who was in the practice at the time, but men who saw the potential that I had and were willing to invest time into helping me along the way. And then later, as more women came into the profession, I had some female mentors as well.”

Hudson notes Bruce Beneke, her first boss at Legal Aid, Judge Michael J. Davis, a federal court judge who served as a supervisor during a summer internship and Judge Pamela Alexander, the first Black female judge in the state, who made significant contributions to Hudson’s development during her tenure in Hennepin County, all as her mentors throughout her career. Additionally, Robert Stanich, a supervisor at the Attorney General’s office, played a pivotal role in shaping Hudson’s abilities as an appellate lawyer, teaching her the skills of brief writing and case argumentation.

Outside of work, Hudson enjoys going to the movies with her husband, being outside, spending time with her two grandchildren and reading something other than briefs when she has the time.

As the Chief Justice looks towards her mandatory retirement in three years at age 70, she reflects on her career with contentment. “I can think of no better way to end my career,” she said. “When this is over, I will happily go sit by the lake somewhere and hopefully get a dog […] and walk my dog and know that I was blessed to be able to do something that I love. Because not everybody can say that.”

![[DEBATES] Prestigious colleges: value or hype?](https://www.mvviewer.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/buildings-1200x654.png)

![[OPINION] The dark origins of TikTok's looksmaxxing trend](https://www.mvviewer.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Copy-of-Copy-of-Untitled-Design-1200x675.png)