In 2017, a student journalist from Pittsburg, California, exposed their principal’s fraudulent resume claims, leading to her resignation. In 2019, a high school student from Amherst-Pelham Regional High in Massachusetts revealed his school’s use of prison labor, prompting the district to discontinue the practice. In 2021, students at Townsend Harris High School in Queens, New York, uncovered that a teacher recommended for termination due to sexual misconduct was still employed. Their investigation resulted in the teacher’s removal and was featured on the cover of the Washington Post.

Unfortunately, many student publications face restrictions by their school administration when attempting to report on issues that may make the school look bad. Some schools attempt to shut down their student newspaper entirely, like Northwest Public Schools in Nebraska, which shut down their newspaper for publishing stories covering LGBTQ+ issues, or Mountain View High School in California where their principal canceled the Introduction to Journalism class after their newspaper publishing an article about sexual harassment.

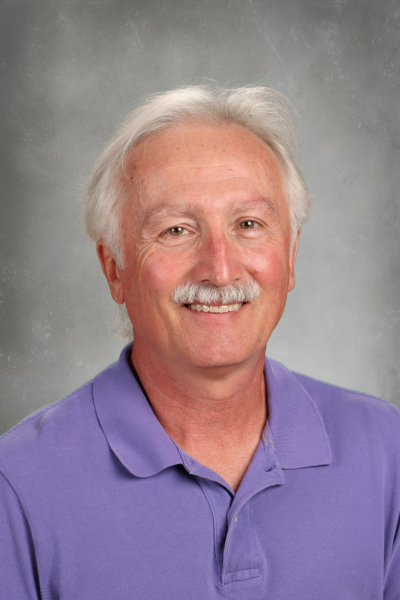

Oftentimes though, school districts will simply impose prior review on their newspapers, which is when school administrators will review content before it’s published. This was even threatened on The Viewer in 2010 after reporting on two students who were suspended for posting a photo on Facebook of their teacher, without her knowing, while a student struck a sexually suggestive pose behind her.

Take it from Martha Rush, who was the Viewer advisor during the 2010 situation which she described as “stressful”: “I think prior review causes student journalists to self-censor and not take on difficult or sensitive topics in their stories, which is unfortunate training for our future journalists and citizens. I think students value free speech more when they are allowed to practice it.”

While some may argue that prior review by administrators is necessary to ensure appropriate content in student publications, it still grants them the authority to potentially censor students. Student publications should never have to face this. During my time as a Viewer editor, Mounds View administration has been relatively supportive of us — supportive enough that I haven’t worried about them restricting us without being open to compromise. Way too many students at other schools are not as lucky.

Unfortunately, prior review from school administration is legal in most states due to the 1988 Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier Supreme Court decision. Like the other examples of censorship, the student newspaper at Hazelwood East High School in Missouri was censored by their school for “inappropriate” articles about teen pregnancy and divorce. The angered staff sued the school, and the case ultimately ended up at the Supreme Court. The Court’s 5-3 ruling in favor of Hazelwood was a major loss for First Amendment advocates. Tinker v. Des Moines, the previous standard for student newspaper rights which established that students’ First Amendment rights are protected as long as their speech does not disrupt the educational process, was consequently overturned.

To protect student journalists from censorship, the New Voices movement, led by the Student Press Law Center, aims to pass legislation across the country that counteract the limits of the Hazelwood Supreme Court decision. Legislation that is necessary for all students to have the freedom of the press they deserve.

In 2016, former journalist Rep. Cheryl Youakim first introduced New Voices legislation in Minnesota, but it was never heard. In 2017 it was once again introduced but never heard. It wasn’t until 2019 that a New Voices bill was approved by the House Education Committee, but even then, it was never voted on by the full House.

After years of struggle in Minnesota, legislators finally passed an omnibus education bill (SF 3567), including New Voices legislation, this April. On May 17, Governor Walz signed it into law. Minnesota has now become the 18th state to adopt this crucial legislation for press freedoms by ensuring student journalists have the right to exercise freedom of the press in school-sponsored media regardless of whether they receive financial support from the school. Additionally, school districts now can’t retaliate against a student media adviser for supporting a student journalist exercising their First Amendment rights.

While SF 3567 does expand the rights of student newspapers, it unfortunately does not include yearbooks. While many students may not see yearbooks as integral to journalism, they still have the opportunity to publish important and controversial stories, but without the same press freedom as newspapers, they are less likely to take those risks.

Nevertheless, passing SF 3567 is a major milestone for student journalists in Minnesota. Still, the other 32 states must continue to work towards ensuring that all students have the rights necessary to hold their administrators accountable, promote civic engagement, bring awareness to important issues and be a voice for the voiceless.

![[DEBATES] Prestigious colleges: value or hype?](https://www.mvviewer.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/buildings-1200x654.png)

![[OPINION] The dark origins of TikTok's looksmaxxing trend](https://www.mvviewer.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Copy-of-Copy-of-Untitled-Design-1200x675.png)

![[OPINION] New Voices Passes in MN… finally](https://www.mvviewer.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/new-voices-1200x982.png)