What happens when religion meets education?

Despite the recent increase in headlines about the incorporation of religion in public schools, this conversation goes back several decades. The topic is still filled with debates over whether the First Amendment rights of freedom of religion and free speech contradict or support the expression of religion in a classroom. The continuous fight extends not just to schools with predominantly religious student bodies, but also to the curriculums taught in schools all over the country.

Beginning as early as when the first European settlers arrived in what is now the United States, religious freedom has long been a core value for many Americans. “This country was founded under religious freedom. That was the whole reason that Puritans and Pilgrims and Quakers came here. They wanted the opposite of what they were coming from, where it was a government religion,” said Ross Fleming, Health and Phy. Ed. teacher and self-proclaimed history buff. To early colonists, part of this religious freedom meant that schools had the freedom to include religion within children’s daily education. The laws around religion in schools depended on the predominant Protestant denomination in each colony with varying focuses and methods.. For instance, Puritan schools in Connecticut used Bible verses to teach students the alphabet while Virginia law required parents to regularly send their children to local church officials for religious instruction.

After the American Revolution, the laws around religion shifted. The passage of the Bill of Rights in 1791 — which established the separation of church and state in the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment — caused churches to lose a great deal of power to dictate the values of the next generations. This caused some panic among church leaders about how children would learn to act morally. However, removing churches’ control was only a small first step to restricting religion in public schools.

In the 1800s, the Common School Movement encouraged education on religion without promotion of any singular denomination. This was done by requiring that common schools — essentially public schools — taught only direct quotations of the Bible, leaving any interpretation to instructors outside of the schools, such as parents. Despite finding great success in the Northeast — especially Connecticut — and the Midwest, the movement still received criticism from non-Protestants, such as Catholics. By the mid-1800s, common schools began to lose their influence due to the many issues dividing Protestant society, including a desire to localize control of schools, as well as debates around slavery and immigration. Additionally, private schools began to emerge around this time, emphasizing the common schools’ decline.

During the Progressive Era in the U.S. — late 19th century to early 20th century — several reform movements spread across the nation. One of these was the Progressive Education Movement, which aimed to universalize education and limit the differences in education styles that existed prior. By shifting the primary focus of education from religion to subjects that increased students’ problem-solving skills like math and sciences, the movement indirectly led education to become more secular.

Around this time, the Tennessee Supreme Court case Scopes v. State gained attention all over the nation, and even the world, as people considered the importance of teaching evidence-based science as opposed to strictly religious concepts. In 1925, John Scopes was charged with violating the Butler Act, a state law that prevented the teaching of any biological theory that contradicted biblical divine creation. Scopes was found guilty of teaching Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution and fined $100. However, the verdict was later overturned as the Tennessee Supreme Court decided Scopes was excessively fined, and years later in 1967, the Butler Act was repealed.

In Engel v. Vitale (1962), the Supreme Court ruled that school-sponsored prayer violated the Establishment Clause of the Constitution. This clause prevented the federal government from declaring a national religion in the United States, designating the U.S. as a religious melting pot and limiting religious bias. “I worry that in some ways, the framing of religion in schools is a way to ‘other’ kids and to center other kids as a priority. In the same way, we pass a lot of legislation to try to open up and be more open, and I worry that sometimes when you bring faith in schools, it’s not a matter of opening things, it’s a matter of closing things,” said Justin Benolkin, social studies teacher.

Further considering the curriculum taught in schools, in Edwards v. Aguillard, a 1987 case, the Supreme Court decided that Louisiana’s Creationism Act — a law requiring any education on evolution to be taught alongside religious beliefs of creation — violated the constitution because it promoted only one religion as an alternative to scientific theory.

Since then, more restrictions have been placed on allowing overt religious practice. For example, the 2000 Supreme Court case Santa Fe Independent School District v. Doe prohibited school-sponsored prayers at sports games, mainly football. Nearly two decades later, a 2019 survey conducted by the Pew Research Center found that only 8% of students at public schools in the U.S. have ever had a teacher lead them in prayer, and the same percent have had the Bible read to them and referred to as an example of literature, depicting the extent to which laws restrict religious bias in public schools.

Although public schools have limited actions such as prayer, there are still plenty of religious students. “When I see the current debates about it, I see it framed around the idea that kids these days are less religious or less moral. And I have a big problem with that being the case when the evidence doesn’t seem to say that. You’re making decisions not based on evidence, but based on what you feel,” said Benolkin. While there has been a decrease in religiosity between this generation of adolescents and their parents, this change is far less extreme than most people believe. According to the 2019 Pew Research Center survey mentioned earlier, 85% of adolescents reported belief in God or a universal spirit, comparable to their parents’ 89%. However, in the same study, teens were more likely to question this, with only 40% saying they are absolutely certain of their belief, compared to 60% of their parents.

Throughout American history, religious education has been a contentious topic with both sides using the First Amendment to justify their arguments. In an attempt to embrace the country’s religious diversity, measures by the U.S. government have undeniably led to less religious partiality in educational settings. Yet, contrary to popular belief, this does not mean that students are completely doing away with religion. In fact, evidence from the survey shows that religiosity is present at nearly the same rates as earlier generations, with critical thought and consideration about these beliefs expanding.

The controversy of the separation of church and state has sprung back into relevance in the past two years. With several states passing bills related to religion in schools, the debate filters into the daily lives of students, and the question of whether bringing religion into public schools is constitutional floods the national stage.

Louisiana, Florida and Texas have changed the view on religion in education. Texas passed a law in 2024 that encouraged public schools to adopt a Bible-based curriculum. This law follows suit from a bill passed in the Louisiana legislature that required the Ten Commandments to be posted in all classrooms beginning in 2025. Florida, similar to Texas, permits the Bible to be studied in all classrooms across the state.

These states are a part of the U.S. region labeled the Bible Belt, which has some of the highest church attendance, with religion playing a large part in their culture and the laws passed in their legislatures. The belt does not have an official border but most commonly includes fractions of Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, the Carolinas and other Southern states according to a survey by YouGov.

Whether the laws passed in the Bible Belt about religion are constitutional or not lies in the First Amendment. The amendment states that the nation cannot establish a national religion. Pushing a Bible-based curriculum does not establish a national religion, but some believe it is a step in that direction. “There’s so many different religions that the state shouldn’t adopt one to try and rule over everybody,” said senior Ellie Dostal Dauer.

Others believe that just posting the Ten Commandments does not necessarily promote religion, but is rather just a sign of school values. “I think schools in the South shouldn’t be forcing children to read the Ten Commandments, necessarily. But if they’re saying, ‘This is what our school’s values are based on, these [commandments],’ I think that’s one thing,” said senior Asher Compton. “Then it’s up to the individual and their parents to decide if that’s a school they want to go to.”

Some believe that states are just representing their religious population and that religion is so enshrined in U.S. history that the government cannot exist without it. “Bible verses are still inscribed on government buildings, so the separation of church and state, how could that possibly be real when Congress began sessions in prayer, the Supreme Court began sessions in prayer? So if religion isn’t supposed to be a part of our public life, why is all that there?” said Health teacher Ross Fleming.

Minnesota has seen less of a push in its own legislature to have a Bible-based curriculum, allow religious documents in classrooms or include any other strong presence of religion. As of now, Minnesota public schools require neutrality towards religion. “I think some of the values that are in religion definitely do align with how people should be treated. But in the way of trying to force religion onto people and force them to participate in a certain religion, I don’t necessarily agree with all of those aspects,” said senior Ben Arnold.

However, the ban of school-sponsored prayers and other religious gatherings does not stop independent groups from showcasing and practicing their beliefs on school grounds. “If you are a practicing Christian and say you need to pray at 12 o’clock exactly, then I think the school should accommodate that, but if they are accommodating you and not other religions, then I think that’s what I don’t like,” said Dostal Dauer.

Although not as prevalent, schools across the country have faced lawsuits from people accusing the school of indoctrinating students into another religion — that religion disproportionately being Islam. For example, in May 2019, a lawsuit was filed by a student against Charles County Public Schools. The student, Caleigh Wood, made the argument that the school had begun promoting Islam under the guise of teaching history. However, the Supreme Court refused to hear her case after the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled against her.

Regardless of the religion, the debate over religious freedom and education will continue to take center stage in these next few years. “People should be free to practice their own religion, as said in the constitution. So when we are implementing things such as readings of the Bible in schools, while yes, that caters to one religion, there’s a ton that is being left out. It’s just not good for the students who are facing that prejudice,” said Dostal Dauer.

At Mounds View, there has been an increasing presence of religious expression among students, including more talk about religion and expression of faith. “I’ve noticed that a lot more of them are wearing religious shirts, clothing … and that’s something that’s new,” said Social Studies teacher Justin Benolkin. This trend reflects the growing openness around religious identity within the Mounds View community.

Christian clubs at Mounds View like the Breakfast Club and the Fellowship of Christian Athletes (FCA) provide students with a space to discuss faith, personal growth and how to navigate school while maintaining their beliefs. “In our meetings, we often talk about how to stay grounded in our faith during the challenges of school. It really helps me focus on what matters most,” said junior FCA member Ted Chresand. FCA meetings typically involve Bible studies and testimonies, but they also address current events and what it means to be a Christian in a public school.

Beyond faith-based discussions, FCA members aim to foster community and create a positive presence in the school. “People who are seeking a deep relationship can come together because [it is] not very often where a group of 50 high schoolers can get together and just have a deep conversation that usually gets overlooked at school,” said Chresand.

Like the FCA’s efforts to create a space for Christian-based community, the Muslim Student Association (MSA) at Mounds View serves a similar role for Muslim students. The MSA provides a space for prayer, discussion and connection, while welcoming those interested in learning about Islam. “We wanted to create a space where people could pray amongst each other … and just feel more comfortable in being a Muslim,” said junior Nuha Adan, a leader of MSA. In addition to fostering this community, the group works to dispel misconceptions and answer common questions.

The MSA also advocates for accommodations like a school prayer space and alternative locations for fasting students during Ramadan. School prayer time takes place in Kauls Court, spanning from 1:30 to 1:50 P.M. for boys and 1:55 to 2:15 P.M. for girls from Monday to Thursday every week. “Having a prayer room and certain time for students to pray feels as if they’re more included in the school,” said junior Sulema Abdi, another leader of MSA. While fostering understanding, the MSA emphasizes that the goal remains inclusivity. Leaders hope to expand outreach through collaborations and broader discussions on diversity.

Teachers at Mounds View face the challenge of navigating sensitive topics in their classrooms, especially when scientific theories or historical perspectives intersect with religious beliefs. These subjects, such as evolution or the Big Bang Theory in astronomy, often prompt questions and concerns from students who hold strong religious or spiritual views.

Teachers are not only responsible for conveying the material accurately, but also for dispelling misconceptions while respecting diverse perspectives. “I don’t feel the need to do any kind of disclaimer because as a public school educator, my job is to educate students about all the important aspects of biology, and that’s not to address religious conflicts, so I don’t overtly bring that up in class,” said biology teacher Mark Johnson. “However, if a student asks in the course discussion, ‘what about God?’ then I will take the time to say ‘well, we might be looking at this topic from two different perspectives,’ and my job is to help them with the scientific understanding of how life changes over time.”

Johnson believes that evolution is a crucial topic when learning about biology and that students do not need to change what they believe in to understand it. “It’s really important to understand that evolution need not contradict [students’] religious beliefs. It’s a largely American phenomenon, to pit evolution and religion against each other… There’s no reason people can’t be a very religious person, very devout, and still appreciate and understand why evolution is so important to biology,” he said.

Teachers and students alike seem to learn much from these discussions, all while keeping a civil, engaging conversation. “I always personally approach [these topics] in terms of curiosity [and in] a very open-minded way, never trying to tell someone like ‘you’re wrong.’ It’s always like, ‘here’s what I think I know and what I can interpret based on the evidence that I’ve got.’ But other people have interpreted it differently,” said science teacher Jacob Hairrell. At the end of the day, Mounds View teachers have to balance the need for all students to feel comfortable with the material while maintaining their dedication to evidence-based education.

As religious expression becomes more visible at Mounds View, students are finding community through religious clubs, which offer spaces for faith, discussion and support. Meanwhile, teachers navigate the intersection of belief and education, ensuring classrooms remain both inclusive and rooted in evidence-based learning. As faith and academics intertwine, Mounds View continues to shape a space where diverse beliefs are supported and academics are taught with respect and integrity.

-

SpreadClimate change: the clock is ticking...

SpreadClimate change: the clock is ticking... -

SpreadThe Healthcare Crisis: sky high prices

SpreadThe Healthcare Crisis: sky high prices -

SpreadThe overwhelming culture of college applications

SpreadThe overwhelming culture of college applications -

SpreadSchool security

-

Spread2024 Presidential Election

Spread2024 Presidential Election -

SpreadMounds View celebrates 70 years

SpreadMounds View celebrates 70 years -

SpreadThe rising trend of overconsumption

SpreadThe rising trend of overconsumption -

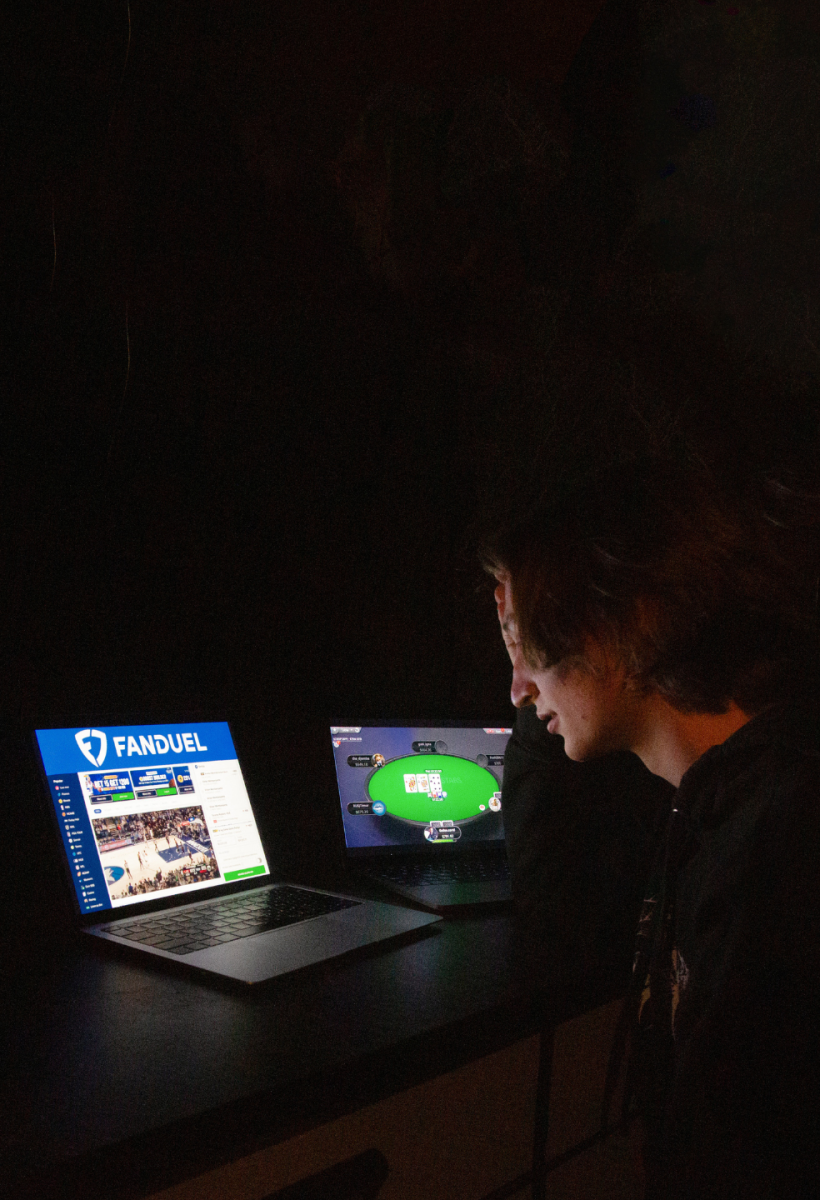

Spread[COLLECTION] The rise of sports betting

Spread[COLLECTION] The rise of sports betting -

SpreadThe downfall of ELA education

SpreadThe downfall of ELA education -

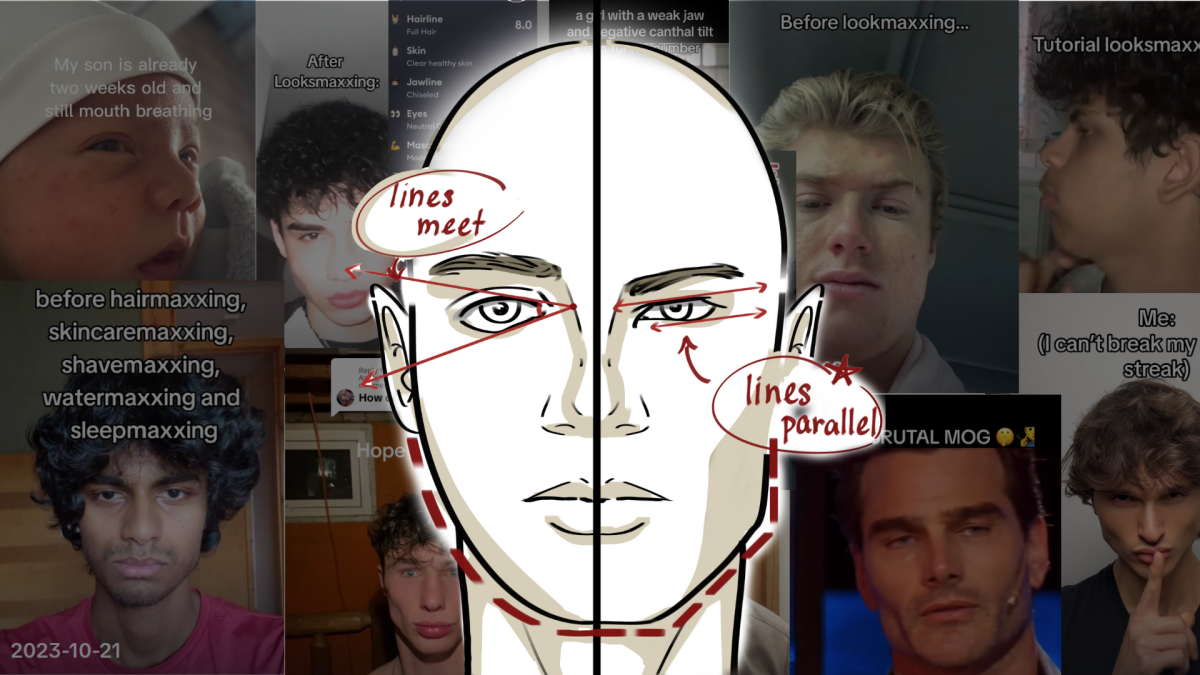

SpreadThe dark side of looksmaxxing

SpreadThe dark side of looksmaxxing